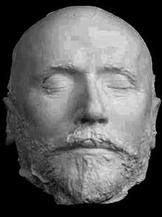

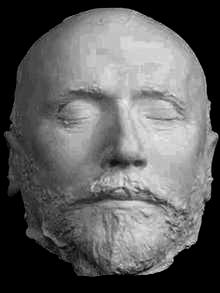

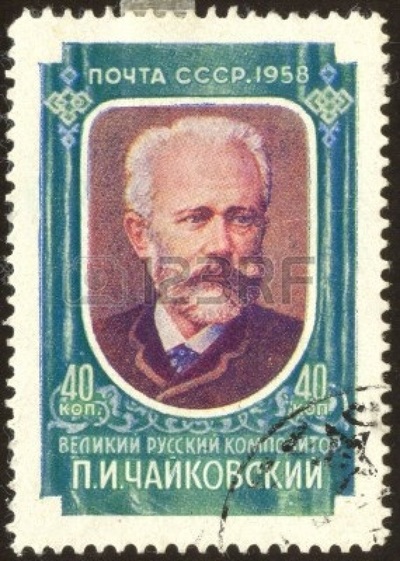

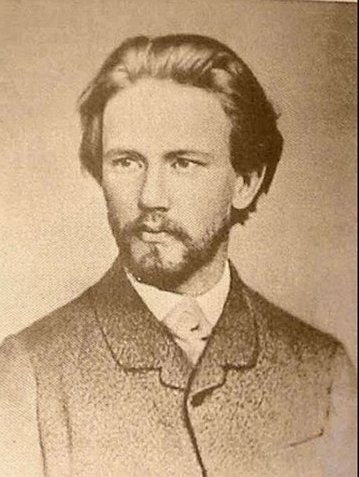

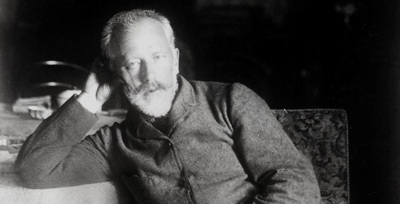

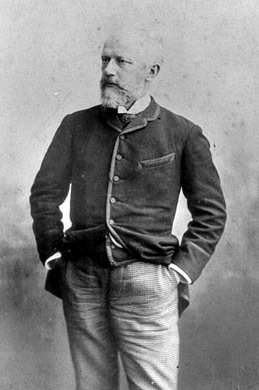

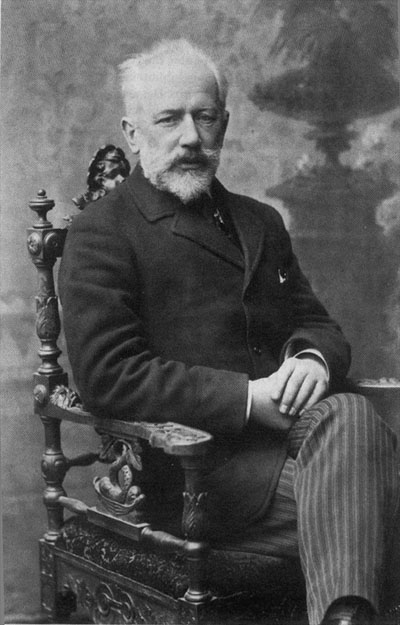

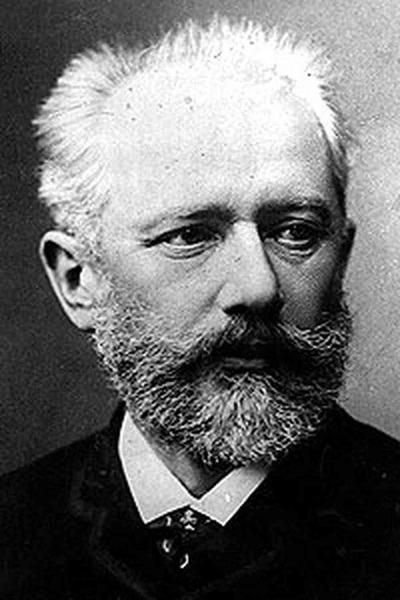

Petr Il'ich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

http://www.tchaikovsky-research.net/

http://wiki.tchaikovsky-research.net/wiki/Main_Page

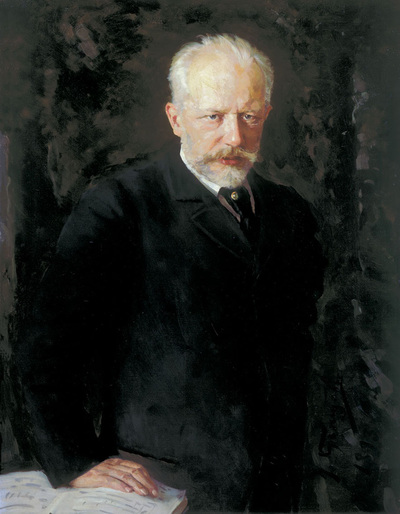

By the end of his fairly short life, Tchaikovsky’s inner and outer circumstances would appear to have been perfectly splendid. After his triumphant tour of America, and being awarded an honorary doctorate at Cambridge University, he was accepted as a world figure, not a merely national composer but one of universal significance. In 1891 the Carnegie Hall program booklet proclaimed him, together with Brahms and Saint-Saëns, to be one of the three greatest living musicians, while music critics praised him as "a modern music lord."

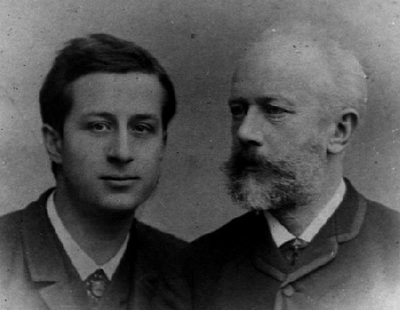

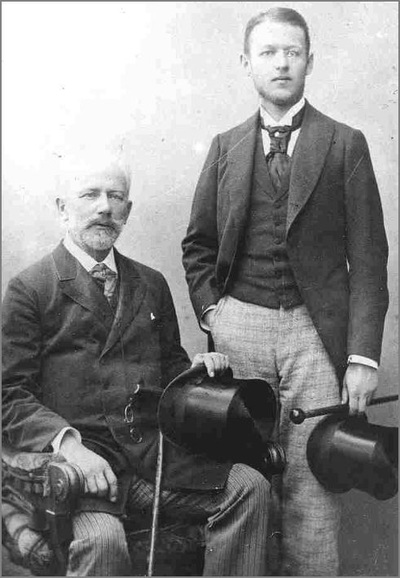

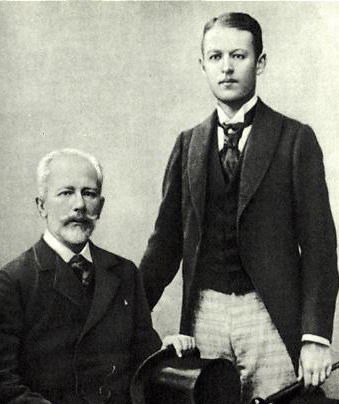

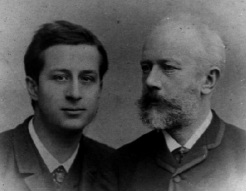

Within Russia he became even more than that—he was considered a national treasure, and his music admired and adored by all strata of society. He enjoyed the favour of the Imperial court, where he had a number of influential protectors (including two Grand Dukes), as well as the personal patronage of Emperor Alexander III, who had granted him a handsome government pension. Regardless of his homosexual orientation, which to a large extent was already a matter of public knowledge, it cannot be said that Tchaikovsky’s inner life had suffered from any prolonged frustration—rather, to the contrary. His main emotional involvement in this period, with his beloved nephew Vladimir Davydov, proved to be a source of stability and spiritual happiness.

Towards the end of the last century, however, the rumours of Tchaikovsky's homosexuality spread beyond Russia's borders, and this effected a change in attitude to his work within Western musicological circles. His music began to be criticized as sentimental, romantically excessive, charged with many imperfections, and even pathological.

Ironically, it was Oscar Wilde's trial of 1895, with its enormous resonance in the English-speaking world, that precipitated negative tendencies in the reception and critical judgement of Tchaikovsky's art. As Richard Taruskin pointed out, that event became a "major watershed in the essentialization and pathologization of homosexuality around the turn of the century… The homosexual was now defined not by his acts but by his character, a character that was certified to be diseased, hence necessarily alien to that of healthy, 'normal' people."

From that moment on, the essentialist curse began to reclaim Tchaikovsky. Almost everything written about his work in America, and in English-language criticism at large, has been substantially affected by the issue of his personal life. The composer’s biographers and music scholars more often than not have chosen to dwell on the matter of his “abnormal” sexuality, employing their own standards as regards sexual morality and health to color their fundamental interpretation of his music. For most of our century a sort of fictionalized figure bearing that name as an embodiment of romantic grief and turbid eroticism, who was supposed by many to have committed suicide as the logical outcome of his sexual lifestyle has continued to lurk behind the inflamed imagination of the lay audience—a caricature that fails even remotely to resemble a real man with real concerns.

Because Tchaikovsky's archives in Russia were recently made accessible to the students of his life and music, we now know much more about him and his environment than we ever did, and it is time to change this fallacious perception of both Tchaikovsky's personality and his art by putting the record straight.

Within Russia he became even more than that—he was considered a national treasure, and his music admired and adored by all strata of society. He enjoyed the favour of the Imperial court, where he had a number of influential protectors (including two Grand Dukes), as well as the personal patronage of Emperor Alexander III, who had granted him a handsome government pension. Regardless of his homosexual orientation, which to a large extent was already a matter of public knowledge, it cannot be said that Tchaikovsky’s inner life had suffered from any prolonged frustration—rather, to the contrary. His main emotional involvement in this period, with his beloved nephew Vladimir Davydov, proved to be a source of stability and spiritual happiness.

Towards the end of the last century, however, the rumours of Tchaikovsky's homosexuality spread beyond Russia's borders, and this effected a change in attitude to his work within Western musicological circles. His music began to be criticized as sentimental, romantically excessive, charged with many imperfections, and even pathological.

Ironically, it was Oscar Wilde's trial of 1895, with its enormous resonance in the English-speaking world, that precipitated negative tendencies in the reception and critical judgement of Tchaikovsky's art. As Richard Taruskin pointed out, that event became a "major watershed in the essentialization and pathologization of homosexuality around the turn of the century… The homosexual was now defined not by his acts but by his character, a character that was certified to be diseased, hence necessarily alien to that of healthy, 'normal' people."

From that moment on, the essentialist curse began to reclaim Tchaikovsky. Almost everything written about his work in America, and in English-language criticism at large, has been substantially affected by the issue of his personal life. The composer’s biographers and music scholars more often than not have chosen to dwell on the matter of his “abnormal” sexuality, employing their own standards as regards sexual morality and health to color their fundamental interpretation of his music. For most of our century a sort of fictionalized figure bearing that name as an embodiment of romantic grief and turbid eroticism, who was supposed by many to have committed suicide as the logical outcome of his sexual lifestyle has continued to lurk behind the inflamed imagination of the lay audience—a caricature that fails even remotely to resemble a real man with real concerns.

Because Tchaikovsky's archives in Russia were recently made accessible to the students of his life and music, we now know much more about him and his environment than we ever did, and it is time to change this fallacious perception of both Tchaikovsky's personality and his art by putting the record straight.

Definitive BBC Bio-Documentary "Discovering Tchaikovsky," #1-7:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Music of Tchaikovsky, a representation:

BOOKS & GUIDES:

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

VIOLIN CONCERTO (mvmt. 1) & Piano/Violin Score:

| |||||||

THE NUTCRACKER [Ballet] SUITE:

| ||||||||

SWAN LAKE [Ballet suite]:

| |||||||

SYMPHONY #5 (1st mvmt.):

|

| |||||||||||||